Main image: Irish jam session at The Old Dubliner pub in Hamburg, Germany, 27 December 2012. The pub’s Irish Session is still held every last Thursday of the month. (Photo by Hinnerk Rümenapf, Wikimedia Commons; CC BY-SA 3.0)

You will find a Norwegian language version of this article in Folkemusikk magazine no. 2, 2018.

I have been wanting to write about Irish folk music – often simply known as “trad” – for some time. But so far, I have only been discovering, slowly but surely, how little I actually know about the music of The Green Island.

Everyone has heard of Riverdance, which renewed global interest in Irish music and dance after The Eurovision Song Contest 1994 in Dublin. Most have heard about The Chieftains and The Dubliners, who made it big during the 1960s and 70s folk revival and inspired thousands the world over to start playing either Irish music or their local folk music. A select few will know that Enya started her career in her family’s crossover folk band Clannad. People will generally make the connection between Irish trad and Irish pubs – whether these are situated in Dublin, Dubai or Drammen.

Around here is where my own competence also stops. I need to learn. The first glimmer of hope manifests itself at Rauland International Winter Festival in February this year.

London Irishman, Irish Londoner

The festival at Rauland Campus always attracts some Irish students and teachers, and this year Dr. Niall Keegan of the University of Limerick is invited to play and lecture. His lecture on Thursday is clarifying, outlining the rhythms, instruments, techniques and typical modes of variation prevalent in Irish trad. The main distinct regions of Irish trad, Keegan tells us, are Donegal, North Connacht, East Galway, East and West Clare and the mountains of Sliabh Luachra. (We are asked, though, to take this division of The Green Island “with a pinch of salt”.)

Keegan himself is from none of these regions, but from just outside London, England. His father is from Wexford in Southeast Ireland, a city founded by Scandinavian Vikings and better known today for opera than for Irish trad. His mother hails from Leitrim in the Irish Northwest, described by Keegan as “Sligo’s poorer cousin” and a region steeped in traditional culture. During the massive Irish immigration to England in the 1950s and 60s, Niall’s parents settled in Kent. In 1990, their son moved “back” to Ireland, where he has now spent more than half his life.

“To Irish people, I’ll always be English, and, to English people, always Irish!” he smiles as we finally sit down for a chat on the very last day of the festival.

The Irish community in the London area was tightly knit and quite segregated, Niall explains to me. Music was central to social life, and he and his sister were sent to classes in both classical music and Irish trad.

“The greatest thing about being in Ireland, another English-born Irishman who moved back to Ireland told me, was he didn’t have to turn off the Irish music on his car stereo when stopping for a red light. This he had always done in England, in order to not be identified as Irish! We made ourselves invisible, and cultural life was pretty inward-looking, cultivating Irish music, Gaelic Games sports and the like. There were some great communities, though I’m not sure how healthy it all was. But I believe migration is inevitable, so we might as well make it a positive thing.”

Is there a “London style” of Irish music, then? Keegan himself brought up this discussion in his lecture, as it’s an interesting and slightly touchy subject. There are some famous trad musicians to have come out of London, people such as John Carty, John Blake, Lamond Gillespie and Brian Rooney. In Ireland, you might occasionally hear their music described as “London style”. The musicians in London themselves, though, wouldn’t agree at all, Keegan affirms – perhaps unsurprisingly, they prefer to have their music rooted somewhere in Ireland.

I believe migration is inevitable, so we might as well make it a positive thing.

It’s an Aesthetic Thing

Conscious of his twin role of academic and musician, Keegan complains that, frequently, academics are interested only in topics that the people in the studied communities themselves couldn’t care less about.

“I’m always cautious in any research I do – when I get the chance to do research! – to keep it relevant to the people actually playing the music. This way, my research can actually impact on the way the communities see themselves,” he states.

He admits he sometimes gets into trouble for this, e.g. questioning the language trad musicians apply to their own music. In discussions on the internet, he is called, amongst other things, “obsessed with politics”, “a middling technician”, or simply and briefly “a crap player” – he certainly stirs the feelings of many. “What’s wrong with the myths and fantasies?” one commentator on thesession.org writes in a discussion about Keegan’s article Let Go of the Language of the Past. “Personally, I would prefer the magic to the cold hand of academe sterilising the music at birth.”

“The fact that the categorisations exist ‘only in the musicians’ heads’, makes them all the more beautiful – and more interesting academically!” Keegan counters. “And I firmly believe that you can’t be neutral if you’re part of a community – you have to be seen to take sides. All I can do is critically engage with the music and the communities – and perhaps ask some questions that others don’t.”

The greatest danger of being an academic is, you might end up appreciating everything and not really liking anything.

So, are there regional conflicts in Irish music? I ask. Not necessarily conflicts, Keegan replies; but historically, some regions, such as Clare, Sligo and Donegal, have undoubtedly been viewed as more important than others. If, in the olden days, you played a tune in a competition from a region considered to be “lesser”, you might actually get disqualified! But he believes people are generally more open-minded these days.

“That desire to define what’s Irish and what’s not has diminished – we are more comfortable with our different ‘Irishes’. But an important aspect of enjoying music is preferring certain styles and musicians and not liking others – it’s an aesthetic thing! The greatest danger of being an academic is, you might end up appreciating everything and not really liking anything.”

And that, he adds, he worries about more than anything else. At The University of Limerick, where Keegan helped set up the folk music programme, they make sure to develop both the hearts and minds of the students – so they become both theoreticians and musicians.

“We believe that, if you are a performer and don’t think about your music, you won’t be a good performer; and if you don’t play yourself, you cannot comment on the music in an equally meaningful way. Our students work very hard, and at the end of graduation play an hour-long gig and write a 10,000-word thesis. They also do a vocational work – a recording, an instructional book, a business plan for their band or something similar.”

In Ireland, there are few music courses specifically aimed at folk musicians – a fact that doesn’t worry Keegan. He believes that trad music students can learn a lot from engaging with practitioners of other styles.

“There is always the danger of becoming isolated when studying at a genre-specific institution, he says. – And the skills that a bass guitarist and a traditional flute player need are often the same. At the end of the day, we will both spend some time filling out the same Arts Council applications!”

The Vertical and the Horizontal

Back in the day, those Arts Council applications might well have been processed by Dr. Liz Doherty, who today works as a traditional music lecturer at Ulster University in Derry, Northern Ireland. As opposed to Keegan, Doherty was born and raised in Ireland. County Donegal sits at the northern end of the island, west of Northern Ireland, where she was born in 1970. She became a musician through the Irish cultural school system.

“We were some thirty-plus children playing together. First, we all played the tin whistle only, but after some time we each got to choose our own instrument. I chose the fiddle.”

There was some music-making in Doherty’s family, and a fiddle-playing uncle, who played both classical and trad music, lived nearby. Doherty describes the learning process at the cultural school as a painstaking one. The teacher would write the tune on a blackboard using letters, and then, pointing at them with his bow, would get the pupils to find and play the notes on their instrument. Slowly but surely, the notes were fitted together into a tune.

“This way I didn’t learn very many tunes until I was older and able to access tunes and teach myself. But we were tight, sounded good and competed annually at local and national Fleadh Cheoil every year, winning numerous awards.”

Fleadh Cheoil is Ireland’s equivalent of the Landskappleik. Young and old first compete regionally in district competitions, and the best ones qualify for the annual nationwide Fleadh Cheoil na hÉireann. Like its Norwegian counterpart, it moves from town to town, but unlike Landskappleiken it is often held in the same place for two or three consecutive years.

Today we need to make a convincing case that playing traditional music is as valuable as composing new music.

Like in Norway, there is a drive towards musical excellence among the young these days, Doherty explains. In her time, the sense of community, of working together, was central to the methodology. There were of course children who were hungry to move forward at a higher speed – but these had to find their own ways to make that happen.

“These days, it’s more common to see classes divided according to both instruments and levels. If, back in in the 1970s, I had wanted to speed up my learning process, I wouldn’t have known how. I caught up just before I started university – at some point learning twenty new tunes a day!”

Doherty has written about this academically, distinguishing between what she calls vertical and horizontal learning. The vertical perspective provides a sense of musical and social history, of tradition; the horizontal is learning from here and there, from different musicians and other sources. Given that, today, everyone has access to all the music of the world, including all of Ireland, the horizontal is increasingly becoming the norm, Doherty notes – and with it, more “trad-flavoured” music with unclear roots is made.

“For me, where the most significant spark happens, is where the horizontal and vertical meet,” Doherty states. “But these days, I really think there is a disconnect between the two. The opposing pressures of novelty and tradition have always been part of tradition. But today we need to make a convincing case that playing traditional music is as valuable as composing new music.”

She points out that parts of the traditional repertoire have survived for hundreds of years – whereas some of the “folkish” music composed today is soon forgotten. In this sense, newly composed trad music is not traditional in the same sense that old trad tunes are.

“Performers of new trad and trad-flavoured music want to keep their claim to tradition because it provides authenticity. But when it moves so far away from the tradition as to be unrecognisable, why not call it something other than trad? I am not a fan of using tradition in a tokenistic way, as part of a global music persona and not doing justice to any tradition, least of all your own.”

Always Alert

Government support structures, Doherty adds, also tend to favour new compositions over playing and re-interpreting a traditional repertoire. In 2005, she herself came to work for the Irish Arts Council, after first giving up academic work in favour of a full-time musician’s career.

“After a while, I started missing the writing and critical engagement of academic life, and I started doing some consultancy work. Then, wanting to write a book about my own fiddle teacher, I applied for some funding but didn’t get it. I got quite offended by this!”

Her feeling back then was that The Arts Council didn’t really appreciate trad music. At the same time, she realised she could only change the system from within. And so, when a position came up, she “took a gamble”, applied and got the position.

“Now there I was, for two years agitating for more funding of trad music! I helped set up a funding scheme for trad, called Deis, and also a mentoring scheme similar to what The Arts Council already had for opera and some other expressions. I did change how The Arts Council engaged with trad music – and, in turn, people in the trad community itself saw the need to make a convincing argument for themselves.”

Traditional musicians all over the world have more things uniting than separating us.

Doherty describes a rollercoaster, with hard and better times alternating; one reason surely being, she admits, how easily one becomes complacent. She urges her trad colleagues to continue stepping up the game, making sure trad music always gets its due.

“Funding is crucial, but even more so is validation and acknowledgement – the badge of honour of being politically important. I absolutely feel trad music – in all its guises – is still not as supported and as subsidised as it should be. To be fair, and I say this as a member of the community: the trad community doesn’t always have its act together – and then it’s difficult to convince anyone else to push it to the top of their priority list.”

Since 2007, she’s back to being Dr. Doherty, lecturing on trad music at Northern Ireland’s Ulster University in Derry. She also occasionally tours with Annbjørg Lien in the multi-national fiddle group, String Sisters. She keeps up with the latest developments in Nordic folk music the best she can.

“Traditional musicians all over the world have more things uniting than separating us. We are always a minority, by necessity always driven by passion rather than money. Still, we want to feel recognised, feel we are valuable, important. We balance staying artistically relevant with not selling out – a permanent paradox! In the Nordic Countries, it seems to me, artists are supported and funded to be who they want to be.”

Eye of The Tiger

Now, how did Irish folk music become such a global phenomenon? Doherty explains it was all part of the 1960s and 70s global folk revival, as in so many other countries. The acts who came out of that era did a massive amount of work setting the stage for trad music globally.

“Folk festivals sprung up around the world, and in Ireland there were artists ready to tour – all with fresh and exciting new ideas for presenting Irish music. All of the stars aligned at that moment! There was also an Irish diaspora, with lots of communities who were ‘more Irish than Irishmen’ around the world, making up a substantial audience who responded enthusiastically to what was coming out of Ireland.”

These first global Irish musicians had a massive impact, leading the way for others. Younger artists took their ideas and adapted them to their own traditions. At the end of the 1970s, Celtic Music was established, showcasing both fusions and local musical forms of Ireland, Scotland, Brittany, Galicia in Spain, Eastern Canada and other regions where a Celtic identity is found.

The 1980s were somewhat of a drought period for folk music in Ireland and elsewhere – and then, in 1994, came Riverdance. For the first time, Irish traditional dancers were given an outlet for professional performance, and there were musicians ready to accompany the dancers.

“Those were the days we Irish really punched way above our weight class!” Doherty states. “Trad music communities all around the world looked to Ireland for inspiration and guidance. But after the ‘Celtic Tiger’ went silent, there has been no follow-up in Ireland.”

Now, the Scottish trad community has overtaken the Irish, she declares – both artistically, creatively and in terms of funding. Doherty believes Irish trad doesn’t have the same freshness these days, in comparison with both Scotland and the Nordic Countries. The huge Celtic Connections festival in Glasgow has certainly given the Scottish scene a massive boost; Doherty finds similar initiatives are sorely lacking in Ireland.

“Infrastructure hasn’t caught up with the needs of the modern music business. We have hardly any managers or agents, no big festivals; we have the Fleadh Cheoil competitions, and grassroots events focusing on bringing the Irish diaspora home to visit. There is a need for professionalising traditional music, to support and sustain the careers of those who want to go down that road.”

A listener will recognise the craftsmanship of good music, the strength and durability of tradition. There’s something wholesome about traditional music.

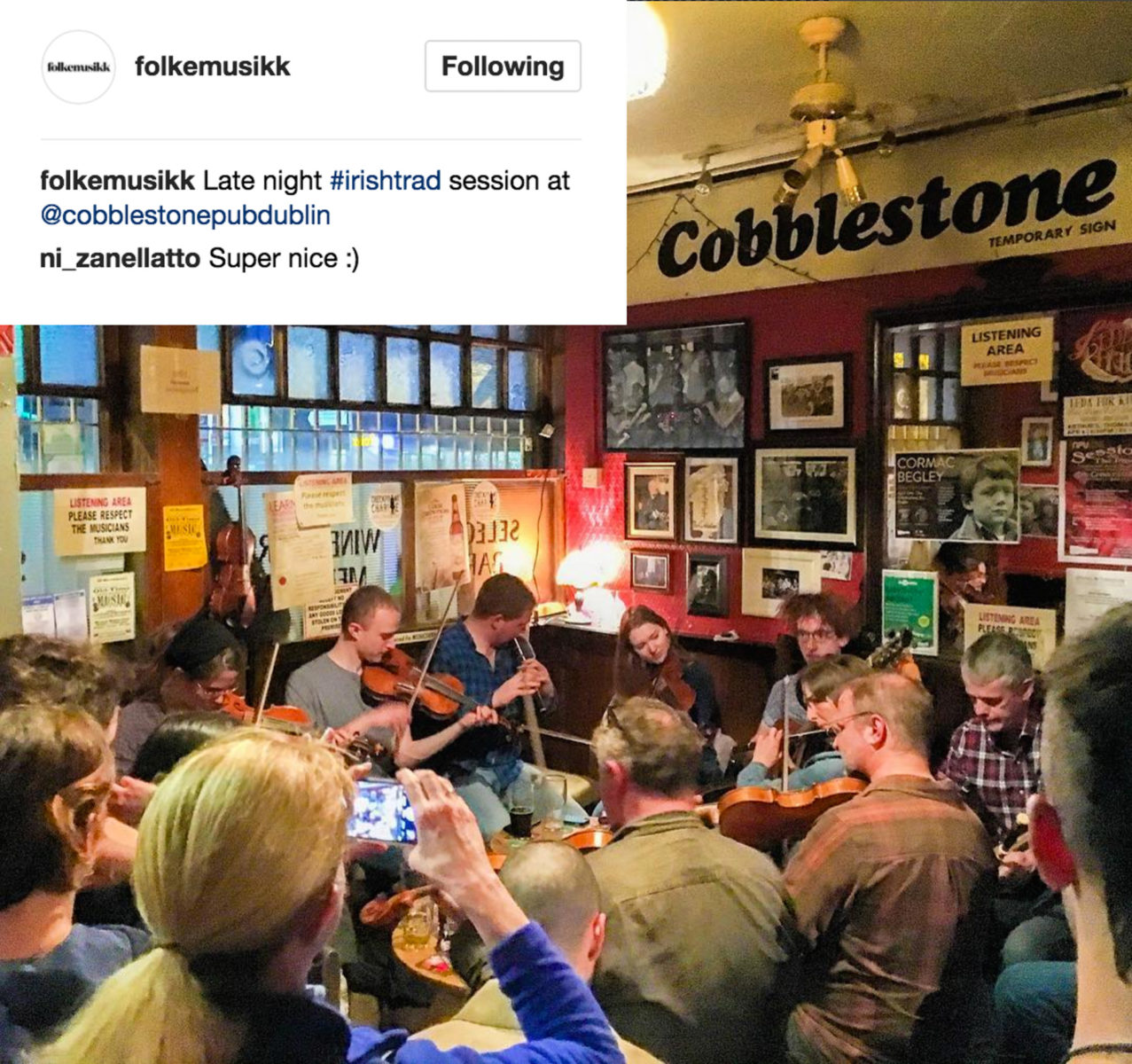

At The Cobblestone

That road brings me back to the start of my “Irish journey” – The Hilmar Festival in Steinkjer, November 2014. Here, festival director Johan Einar Bjerkem introduces me to Mr Tom Sherlock, a Dublin music manager who has recently ventured into Nordic folk music. He was invited to Midtnorsk Musikkmesse (Central Norwegian Music Conference) to speak about how Irish traditional music and dance found an international audience.

An underlying question is, of course, how to export Norwegian trad music and dance. The Hilmar Festival itself has, since Sherlock’s visit, branched out and started an artist management division of their own. It’s easy to imagine Sherlock’s talk having inspired this venture; a major point for Sherlock is that because it happened in Ireland, it can happen anywhere.

So, how does one strike the right balance between traditional authenticity and professionalism? How did the Irish make it? I have previously asked Sherlock to write an op-ed piece for Folkemusikk magazine on the subject, but he has been busy. Now it is April 2017 and I am headed for Ireland myself, so I ask Sherlock if we could make it an interview instead. He happily agrees.

The centre of Dublin, at first glance, looks like any mid-sized British county town. What’s all the fuss about? I soon discover, and find I’d like to spend my time at The Cobblestone pub. This institution of Irish trad sits on a nondescript street corner at the heart of Smithfield, a working-class district that was once part of a hamlet north of Dublin itself: Oxmantown. That name is a corruption of the Norse Austmannatún, the homestead of the “Eastmen” – the Scandinavians, that is. History, the main draw of Dublin beside the amiable Irish themselves, soon starts revealing itself in Dublin’s smaller details.

After a couple of nights at The Cobblestone, run by the musical Mulligan family, Dublin is all the more appealing. Two traditionalist chaps, by the proper Irish names of Colm and Fergus, each buy me a Guinness and make sure I get value for my money. I am generously told about historical Dublin landmarks and the various invaders and settlers of The Green Island through the times. All the while, the proper Irish sounds of fiddles, flutes and stringed instruments flow from the musicians’ corner by the entrance.

On my last day in Dublin, Tom Sherlock picks me up in his car and takes me sightseeing. We drive south through Irishtown, so named because Irish-speaking people settled there, outside the city walls, after being expelled from Dublin in 1450. Soon the winding city streets give way to pleasant suburbs of villas facing the Irish Sea. The roads twist up and down lush green hills, past the homes of Bono, Enya, Van Morrison and other folk-pop royalty. After half an hour we reach Monkstown – not surprisingly owing its name to an ancient monastery – where we stop for lunch.

Tom Sherlock started working for the trad music company Claddagh Records in 1982, with only a limited knowledge of the music back then. For the last twenty years, he has managed a string of Irish artists, including Altan, Lúnasa, Liam O’Flynn and Karan Casey. These days, he is the manager of Danish–Swedish trio Dreamers’ Circus and the Dublin quartet Lankum. The latter is described by Dr Niall Keegan as a modern-day Dublin ballad band, compellingly modernised, made grittier and more realistic.

“Irish music was invisible in Ireland too; then it changed,” Sherlock says. “The same can easily happen in Norway. But I always start by insisting that I never tell anyone what they should do. I can only tell you how things happened in Ireland.”

His statement might sound meticulous, but it’s only a realisation that how a trad movement manifests itself and develops is influenced by many things – the history of genres, the frame of mind of individuals and collectives, the will and whims of particular movers and shakers.

Can I Have Some?

What Ireland had, and what the world was waiting for, was music that was seen as authentic, Sherlock emphasises. Authenticity was the main selling point back in the 1960s, as it was when he started managing artists in the 1990s – and still is today for millions of music lovers. For most, it doesn’t much matter whether the authentic music is West African, Nordic or Irish, Sherlock believes.

“A listener will recognise the craftsmanship of good music, the strength and durability of tradition. There’s something wholesome about traditional music,” is the way he puts it.

And Nordic trad, he insists, is just as worthy of global recognition as Irish trad. But the first step to success is to have a music business. Business and accounting is, after all, best handled by people with such skills. That way the artists may concentrate on their skills, and being creative is hard enough as it is. Sherlock suggests there is something to gain by making sure there are support structures in place for people who want to try their hand at the business side of things.

“Not necessarily huge sums, but grants to be able to play at international showcases and other important meeting grounds, and bringing a manager along to an event. And artists themselves need to be export ready – so that if all stars align, they are ready to go.”

80% of tourists cite cultural reasons for travelling to Ireland. People still come to Ireland to study and learn proper Irish dancing because of Riverdance.

At the same time, in Ireland as well as in Norway, the most dangerous label to have attached to oneself is selling out. Is Riverdance representative of genuine Irish tradition? Would Irish trad be better off without Riverdance, without The Corrs – the sibling quartet that still plays a set of Dundalk reels at every show – and without the hundreds of jam sessions featuring more or less Irish music, at more or less Irish pubs, around the globe? A musician transforms a traditional dance piece to fit it into his global tour; at what cost to tradition? Opinions differ, as Sherlock well knows.

“I know people who still insist there is no place for the guitar in Irish folk music because at some point there were no guitars! What I always insist is that Irish trad is contemporary music. It’s rare to see an Irish trad artist dress up in traditional costume and emulate something old.”

Concertinas and two-row button accordions entered Irish trad music some hundred years ago and, today, are essential parts of it. So are the banjo and other instruments of African and/or American origin. People should embrace change, Sherlock proclaims; whether one likes it or not, the music keeps changing, and democratically so.

“Change doesn’t spell doom for tradition – quite the opposite. Your own Hardanger fiddle music is cool, it has its own ethos and it’s fun – and that is how you keep a tradition alive. When The Chieftains made Irish trad big in the 70s, all of a sudden people started asking, ‘What is this?’, and ‘Can I have some of this?’ And the image of Ireland changed, its association changing from famine and poverty to green hills and cultural abundance.”

Even though, as Niall Keegan puts it, Irish folk and similar genres are “no longer on top of the European folk festival menu, but rather in the middle”, it has a continued presence on the global scene. Artists have avoided “ghettoisation” and are touring the popular music market, something Tom Sherlock believes is a prerequisite for the continuous success of the music. And perhaps most importantly for all non-musicians, Ireland has succeeded in creating a cultural economy.

“This economy is also essential to our tourism,” Sherlock emphasises. “80% of tourists cite cultural reasons for travelling to Ireland – and that is mostly music. Purists don’t love Riverdance, but it has brought an audience of millions to Irish trad – people who, without Riverdance, might not have known this music existed. People still come to Ireland to study and learn proper Irish dancing because of Riverdance – I’m sure the Norwegian trad community would be delighted if the same happened in Norway!”

Sherlock believes in the global success of Nordic folk music, which as manager of Dreamers’ Circus he himself is invested in. And many things Nordic are already wildly popular all around the globe. Sherlock himself readily admits to owning, and loving, a certain Norwegian book on stacking wood – of course referring to the unlikely, and thoroughly hyggelige, global hit book Norwegian Wood (Hel ved) by Gudbrandsdalen writer Lars Mytting.

Hygge and lagom have for some years been vying for the title of the trendiest lifestyle frame of mind these days; “Calm down, trendspotters – ’lagom’ is not the new hygge”, The Guardian assured its readers in February last year. It all boils down, Sherlock thinks, to the desire for rootedness among citizens of our restless age.

“This is happening now, but musically it has so far manifested itself through Icelandic or Norwegian pop and rock. This is cool, of course – but why shouldn’t something more rooted be able to hit the same market? No-one would have thought ten years ago that hygge should suddenly be the coolest thing! I send English language articles on hygge etc. to colleagues in the Nordic countries, and they have a laugh – but the authors of these books are not laughing. They make money.”

What musicians should ask themselves, Sherlock concludes, is the question: What suits us? With that conversation, he adds, self-confidence is built. And with that, we leave the café in Monkstown. I take the local train back to Dublin – and head up to Austmannatún for a final night at The Cobblestone. The musicians are confident in their playing, and I am starting to have some more confidence in understanding the phenomenon of Irish trad.